Beyond Inclusion and Reverse Inclusion: how fully engaging with the needs of disabled and elderly people can turbo-charge innovation and profitability

2021 update: Hassell Inclusion are now running Innovation Workshops to help organisations benefit from the innovation that can come from doing user-research with people with disabilities. Check out our demonstration video.

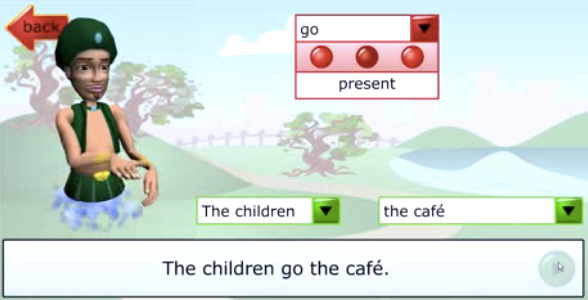

Two weeks ago BBC Something Special launched a great set of Out and About web games for children with learning difficulties.

This is the latest in a category of websites which are aimed at specific disabled audiences – at their particular interests, needs and capabilities.

Other examples I’ve been involved with (mostly with my partners Gamelab UK) include: Us5 interactive videos to help young people with learning difficulties make life-choices;  Performing Hands interactive storybooks and literacy games using signing avatars for children who are Deaf; and Sos and the Big Maths Adventure audiogames for helping blind children learn maths skills.

Performing Hands interactive storybooks and literacy games using signing avatars for children who are Deaf; and Sos and the Big Maths Adventure audiogames for helping blind children learn maths skills.

Back in 2007 I termed these sites produced specifically for disabled people ‘beyond inclusion’ sites, as they took the bold step of going beyond the usual inclusive line – create something for everyone – and recognised that, on some occasions, this might not be the best thing to do.

The two main times you might want to consider creating sites like this are where the needs of some disabled groups diverge from the mainstream due to:

- different content needs: for example, teenagers with learning difficulties may be learning skills other teens have learnt at a much younger age, due to delays in their learning capabilities; they will, however, need materials which are age-appropriate for them, rather than just using materials aimed at mainstream younger learners

- differences in preferred style of information processing or learning: for example, blind children learn literacy in a different way than sighted children due to having to learn to distinguish different Braille characters with their fingertips to be able to read

‘Design for all’ vs ‘Design for me’

Websites to meet these sort of divergent needs raise a challenge to the usual orthodoxy of ‘design for all’ inclusion, with few people outside the educational world (with sites like symbolworld.org and SEN products from companies like Inclusive Technology) understanding their place.

Modern education, in the UK at least, is obsessed with providing a personalised learning experience. It understands that, while you could teach everyone the same way, effective education benefits from understanding and catering for the unique learning style of the individual. That’s what teachers have been doing for years.

Putting this in web terms, while inclusive design can make sites that are usable by most people, effective ‘beyond inclusion’ design takes into account more of the user’s needs and preferences to give them a more personalised user experience.

Because, in reality, no-one really wants ‘design for all’; everyone wants ‘design for me’.

Beyond inclusion games spark creativity

In 2007, for the BBC jam project on which I handled inclusion, the key ‘learning style’ we were concentrating on was games. Educational games. Learning by playing; by engaging, interacting and doing, not just reading about theories.

The great thing about creating games is that it prevents you from doing the lowest common denominator inclusion thinking we often do with websites. The purpose is not to convey some information. The purpose is to have fun. And, in this case, to learn something while having fun.

This ‘fun’ perspective reveals many of our current ideas on accessibility as impoverished. Websites get created to work for non-disabled people, which you hope work for disabled people if you’ve coded them the right way. Accessibility is all about tweaking stuff, slavishly applying guidelines. The most creative you get is to give a blind person alt-text to describe the pictures – using words to conjure up images like a novelist.

For most informational web content that’s fine. But don’t kid yourself that you’re giving people anything more than information. It’s certainly not fun, for the users or the production team. No wonder accessibility can sometimes have a bad name.

But there is another way. A way that comes out of our educational heritage – those pre-Inclusion ‘special schools’ that are slightly out of favour these days. What I discovered talking with teachers from those schools, and the SEN co-ordinators they are trying to pass their experience on to, was true creativity – finding any possible way to help kids learn in a form which means something to them and motivates them to explore further.

A picture tells a thousand words. But how many more does a work of art tell? And would you appreciate Monet’s Water Lilies if you just listened to words on its brush technique? Describing a circle by comparing it to the sun means nothing to someone who has never seen the sun. Whereas tracing the edge of a coin with your finger starts to get across the idea. And moving around the inside a round space like St Paul’s whispering gallery really makes the idea of a circle come alive. How do you describe rhythm to someone who can’t hear? Through barcodes, dance, or tapping out beats on the backs of their hands?

These SEN teachers are masters at this sort of innovative lateral thinking. And it’s fresh, fascinating and addictive; everything that much accessibility thinking unfortunately isn’t.

On BBC jam, I was honoured to have a multi-million pound budget to try and capture some of their lightning in a virtual bottle for kids who are Deaf, blind, or have literacy, language or learning difficulties. To create ‘beyond inclusion’ eLearning games as if they were the only kids in the world. To take the learning goals and the techniques the best teachers used. To get inside the worldview of the kids and see what they found fun. To mash that up with some of the coolest R&D we could find, with guys who knew how to produce games that would keep you coming back for more.

The results were some of the most innovative uses of web technologies I know of. ‘Performing Hands’ advanced the state of the art in signing avatars. ‘Us5’, although made specifically for young people with learning difficulties, was even nominated for Best Children’s Drama at the 2009 Children’s Baftas.

The results were some of the most innovative uses of web technologies I know of. ‘Performing Hands’ advanced the state of the art in signing avatars. ‘Us5’, although made specifically for young people with learning difficulties, was even nominated for Best Children’s Drama at the 2009 Children’s Baftas.

So it’s great to see a new generation of ‘beyond inclusion’ mobile apps arriving which take the needs of specific groups of disabled people and find a solution to these via the capabilities of smartphones. While not everyone needs an app that allows you to take a photo of your surroundings and get an automated answer to questions about your vicinity, blind people can really value this from apps like Vizwiz. Robin Christopherson gives a great review of how smartphone apps help him overcome challenges from his blindness, and Vodafone are currently running a Smart Accessibility competition to encourage more apps like this to be created.

How this thinking can help innovation in product design

So is this thinking just for eLearning sites and mobile apps?

Well, no. Going deeper into really listening and designing for the wide range of needs of disabled and elderly people can be very challenging. But innovation often follows a challenge. And innovation is the lifeblood of most successful companies.

Product design teams often use the process of ‘overcoming fixation’ in ideation sessions to come up with fresh and innovative new products. I’ve participated in sessions where the team is encouraged to think for 10 minutes of what an alien might look like, so they can then re-engage with a design problem having shaken their brain out of the same old 8 ideas every other design team has already come up with.

But why dream of aliens when similar ways of inhibiting old ideas and generating new ones are a lot closer? Design an oven for people who have difficulty carrying any weight in their hands. Design a game of golf for people who can’t see. Design a car for people who can only use a joystick to navigate. Design a life insurance policy which someone with an IQ of under 100 could understand. Design a web-TV which your grandmother could use…

Anyone who says accessibility or inclusion constrains creativity just isn’t trying hard enough. For me, it’s the most challenging, creative work I’ve ever had the pleasure to be involved with. Putting together the needs of disabled and elderly people and the possibilities available through emerging technologies is the most fun game in town.

Reverse inclusion takes this to the mainstream

But could you really make money with this way of thinking?

Well, on BBC jam, we also coined a second term, ‘reverse inclusion’, for the slightly subversive idea that disabled kids could invite non-disabled ones into their worlds for a while through ‘beyond inclusion’ resources, to give them a bigger picture of learning. That there might be something which hearing kids could learn from sign-languages. Or that audiogames played solely through what you can hear and feel could appeal beyond the blind community (see Papa Sangre for the proof of that). That engaging the senses you don’t often use in learning could be the fresh impetus you need to find learning fun.

This crossover into the mainstream isn’t new. There are examples of reverse inclusion all around us, and we often have no idea of their ‘beyond inclusion’ roots. The keyboard I’m typing this on was initially created as a tool to help blind people write (thanks, Pellegrino Turri). The OXO Good Grips potato peeler I use was initially created for one man’s wife who had arthritis. The same lifts and kerb-cuts created to help people using wheelchairs cross the road independently also help me take my 2 year old shopping in his pushchair. And I could have helped my son pick up language skills early by taking him to one of the multitude of baby signing classes that are springing up everywhere using signs borrowed from Deaf culture. Gestural interfaces are effectively the non-signing population catching up with what signers have been doing for years. I can tell the name of the track I’m playing on my iPod shuffle while jogging because it uses the same VoiceOver technology that was designed to allow blind people to use a Macbook. Reading iBooks in the night-time is so much easier as iPad designers figured people with some eye conditions would prefer a white text on black option. And what is Siri other than a generation of iPhone users catching up with a slightly more intelligent form of the voice-recognition people with motor difficulties have relied on for years?

The world regularly becomes a better place for everyone when we concentrate on taking the needs of disabled and older people more seriously.

And, yes, there is money to be made.

This is why Hassell Inclusion aims to work on many projects like uKinect – a way of using Microsoft’s Kinect to recognise the Makaton sign language used by many people with learning difficulties that we’re helping Gamelab UK to create at the moment. On Day One it may help students with learning difficulties learn or communicate more easily. But in the future, who knows where it might take us…

If you’d like to take a step into this world – maybe to try the Vodafone Smart Accessibility challenge, to produce something to win awards like those from the Creative Diversity Network, or just to try a new way of overcoming fixation – contact us. With awards like those already on our mantelpieces, we’d love to help you create something amazing.

Want more?

If this blog has been useful, you might like to sign-up for the Hassell Inclusion newsletter to get more insights like this in your email every other week.

Comments

Ian Hamilton says

The tricky thing is that as complexity of disability increases, the need and potential benefit increases dramatically, but at the same time the numbers of people who benefit and the cost per user both increase accordingly, meaning those who stand to benefit the most are the least likely to be catered for.

Thankfully though there’s a nice solution. Content is now separated from presentation as standard. Visual & motor are the obvious areas in which alternative interfaces can help, but even cognitive too, reducing clutter and confusion and adding simplicity and consistency.

The separation between the two means that even the most challenging of audiences can be catered for by a straightforward simple one-off investment, rather than running a separate parallel product with its own ongoing costs.

We did exactly that with teh following project, meaning that it was possible to produce a content-rich regularly updated news website for children with complex and multiple special needs (covering conditions such as autism & cerebral palsy) for a small fraction of what even just a microsite would cost to develop, and with negligible ongoing costs.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/cbbcnews/hi/newsid_8050000/newsid_8059800/8059895.stm

Catherine Amimo says

I got quite some insight reading this article. Just to think how the non disabled child can benefit from maximizing use of his rarely used senses.

Jonathan Hassell says

Absolutely, Catherine! Glad to have inspired you. And thanks for your comment.

Let me know if you come across other examples of ‘Beyond Inclusion’ and ‘Reverse Inclusion’ out there that you think are good.

catherine Amimo says

Currently engaged in a vocational project of reverse inclusion- a case of the deaf and hearing. It is amazing!

Jonathan Hassell says

Sounds great, Catherine. Feel free to let us have more details of what your are doing…